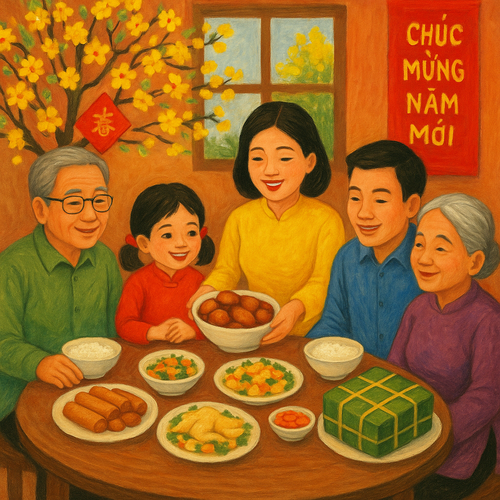

Meals are moments of care, connection, and community. (AI-generated photo) Meals are moments of care, connection, and community. (AI-generated photo)

|

Across Vietnam, China, and South Korea, one tradition sits at the heart of every shared meal: respect for elders, a value deeply rooted in Confucian teachings. This principle shapes not just the tone of a meal, but every small gesture at the table.

“Vietnamese people respect older people. The society is built on Confucian beliefs, where experience and wisdom are highly revered,”Vietnamese tour guide Van Vu explained.

“That means the older you are, the more respect you receive. At a Vietnamese dinner, you may not take your seat until the elders have. You may not start eating until they touch their food. And you may not leave the table until they finish their meal.”

It’s a familiar story across East Asia. Qing Duo, a Chinese correspondent, and Jeon Hyong Jun, Marketing Manager at StyleKorean Vietnam, both describe similar expectations in their cultures.

“In traditional Chinese dining, seating arrangements matter most – the guest of honor usually sits facing the door or farthest from it, while the host sits to their left as a sign of respect. Wait for elders or the host to start eating first. Avoid "digging" through dishes when serving yourself, and try not to slurp your soup,” said Ding.

“In Korea, it's respectful to wait for the eldest person to start eating first. You should also use both hands when receiving dishes or drinks. Keeping quiet while eating and finishing all the food on your plate is considered polite,” said Jeon.

While every culture has its variations, all three share strict taboos around chopstick etiquette.

In Vietnam they often connect to spiritual beliefs, especially those surrounding death, according to Van.

“Sticking chopsticks straight into your bowl is a taboo since it reminds Vietnamese people of a funeral. People often stick burning incense into rice to honor dead people,” Van explained and added, “Don’t knock your chopstick against your bowl. For Vietnamese people, knocking chopsticks against your bowl is like inviting ghosts or wandering spirits to your home, and may bring bad luck to your family.”

These symbolic meanings aren’t unique to Vietnam. Similar sensitivities are found in China and South Korea, too.

“Never stick chopsticks upright in your rice, and don’t point at people with them,” said Duo.

Echoing Van and Duo, Jeon said, “Never stick chopsticks upright into rice as it resembles a funeral ritual.”

Serving food to others is seen as warm hospitality, but refusing can be mistaken as dislike. (AI-generated photo) Serving food to others is seen as warm hospitality, but refusing can be mistaken as dislike. (AI-generated photo) |

Beyond rules and taboos, meals in these cultures are about connection. Communal eating is a key aspect of dining in all three countries, though with nuanced differences. Serving others and sharing food isn’t just politeness, it’s how love and care are expressed.

“Sharing is caring,” said Van, adding, “Vietnamese people share everything on the table. There are usually three main dishes on the table: A protein dish, fish or meat; a vegetable; and a bowl of soup. It's absolutely okay for you to use your own chopsticks to pick up the food from the shared dish. For the soup, though, you should use the utensil that’s already in the bowl. Do expect food to be given to you.”

“If a Vietnamese host is taking care of you, they’ll pick up food from the shared dish and put it in your bowl. Asian people show their love and affection through food and acts of service,” Van noted.

Meanwhile in China, “Serving food to others is seen as warm hospitality, but refusing can be mistaken as dislike,” said Duo.

“Pouring drinks for others, especially elders, is a sign of respect. But don't pour your own drink. Wait for someone else to do it,” Jeon explained the Korean customs.

While there are clear expectations, they aren’t about judgment. In fact, the differences in table manners don’t mean “this is right” or “that is wrong,” but simply show how manners reflect social values and how people care for one another. Sometimes, what seems unusual to one culture carries deep meaning in another.

Take slurping noodles, for example—often frowned upon in Western settings but embraced in East Asian ones.

For Koreans, Jeon said, “Slurping noodles helps them slide smoothly without breaking, which feels really satisfying. It also shows that you’re enjoying the food a lot. In Korea, ramen is one of the most common snacks and you often see commercials of people slurping it. Those ads really make you crave ramen.

“In Japan, loud noodle slurping is a compliment to the chef, but in China, it’s more casual habit than proper etiquette. Older generations might see it as a sign that the food is delicious, but younger people, influenced by Western manners, might find it impolite. It’s still common in casual noodle shops but best avoided at formal dinners,” said Duo.

Unlike Western culture, Korean food is usually not individually served. Instead, people have a big main dish and share it on the table. (AI-generated photo) Unlike Western culture, Korean food is usually not individually served. Instead, people have a big main dish and share it on the table. (AI-generated photo) |

As customs evolve, especially among the younger generation, tradition and modern habits coexist. Formality may be fading, but the core values remain.

"Young people nowadays prefer 'no-pressure dining'. Splitting the bill is totally normal while fighting to pay is seen as old-school. And since the pandemic, health concerns have made serving chopsticks and individual portions more common. Their usage rate jumped from 12% in 2019 to 68% in 2023," said Duo.

“Younger Koreans are becoming more casual. They often skip some formalities, especially when eating with close friends. Still, core values like respect for elders and communal eating remains strong in daily life,” said Jeon.

And still, in Vietnam, hospitality is non-negotiable. A simple act, like bringing a gift when visiting someone’s home, says more than words.

“It's not a good idea to show up empty-handed if you’re a guest. In Vietnam, if the host family has kids, you can bring a box of chocolates or cookies. If they live with elders, you can bring something that’s good for their health like nutrition powder or vitamin supplements,” said Van, adding, “When in doubt, go for fruits, because Vietnamese people love having fruit after their meals. Before eating you need to moi (invite) other people to eat. Moi shows your respect for them,” said Van.

Vietnam, China, and South Korea share core values of respecting elders, communal dining, and symbolic chopstick etiquette. From offering the first bite to ensuring no one eats alone, their dining customs reflect a philosophy: meals are moments of care, connection, and community.