Hello and welcome to VOV’s Letter Box, a weekly feature dedicated to our listeners throughout the world. We are Ngoc Huyen and Phuong Khanh.

A: First on our show today we’d like to acknowledge an email from Pillai.N of Kerala, India. In his email, he wrote: “Your reports on legendary VOV announcer Trinh Thi Ngo were an outstanding homage to her. Your rare and valuable recording of a 1968 English broadcast featuring Trinh Thi Ngo on VOV is most memorable to me. My special thanks to you for these remarkable reports”.

B: Pillai continued: “Colombian President Juan Santos has won the Nobel Peace Prize for this year. Le Duc Tho, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973 along with Henry Kissinger for their work on the Paris Peace Accords, declined to receive the award because peace had not been established in Vietnam. I would like to know more about Le Duc Tho.”

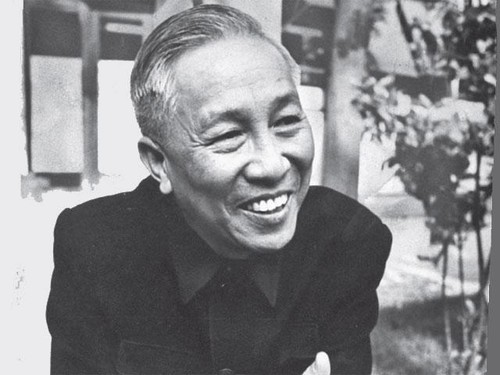

Vietnamese diplomat Le Duc Tho- Photo: Economic Times |

A: Le Duc Tho was the first and only person ever to refuse a Nobel Peace Prize. In his declining statement, he wrote: "Peace has not yet really been established in South Vietnam. In these circumstances it is impossible for me to accept the 1973 Nobel Prize for Peace which the committee has bestowed on me."

B: Le Duc Tho made history with this statement, becoming the first and only person to refuse to accept a Nobel Peace Prize. Le Duc Tho had long experience of fighting against western powers when he negotiated with Henry Kissinger for an armistice in Vietnam between 1969 and 1973. As a young man he became a Communist, and the French colonialists imprisoned him for many years.

A: He gained a place in the Communist Party’s leadership during Japan’s occupation of Vietnam in the Second World War. President Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam independent after the defeat of Japan in 1945, but the French returned, and Le Duc Tho became one of the military leaders of the resistance against the French.

B: After the defeat of the French, Vietnam was divided. The US supported a government in South Vietnam and this led to more conflict in the region. The clash between communist North Vietnam and US-supported anti-Communist South Vietnam in the mid-1960s turned into what is known as Vietnam’s anti-US war.

Diplomat Le Duc Tho (in the middle) |

A: After staggering civilian and military casualties, Tho was called upon to join the Paris peace negotiations in June, 1968. He and US national security adviser Henry Kissinger eventually met in secret in 1969 and several years later following December bombing raids by the US on Hanoi and Haiphong negotiated the January 1973 Peace Accords.

B: Many hoped it would mean the end of one of the most terrible wars of the 20th century, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee rewarded the negotiators with the Peace Prize. The awards to Kissinger and Le Duc Tho became, however, one of the most controversial issues in Peace Prize history.

A: Tho declined the prize and said that it was because the US and South Vietnam had broken the ceasefire. The 1973 Peace Prize stirred heated debate, and for the first time in the history of the prize, two Nobel Committee members resigned in protest.

B: That’s a brief bio of Le Duc Tho, Vietnamese politician and co-recipient in 1973 (with Henry Kissinger) of the Nobel Prize for Peace, which he declined. This week, John Ball of Australia commented on our story about Gongs in the life of the Muong broadcast on October 22. He wrote: “I would like to hear or download Muong and other Vietnamese gong music. I have returned to Australia after 10 years working for Vietnam News and have a large, 7kg gong that I play whenever I burn incense … or feel happy”.

A: Thank you, John, for tuning in to our broadcast. Gong music is sacred to the central highlanders including the Ede, for whom the sound of gongs evokes their origin myth, the Dam San epic.

B: Called Cong or Chieng, gong instruments accompany the celebrations and rituals of the minority peoples who live in the rugged Truong Son Mountains. Echoing through the valleys, the clatter of gongs signals friendship, memories of past festivities and an invitation to join the hamlet in celebration.

A: Long ago, the gongs were made of stone, wood and bamboo, which was later replaced with copper. Each minority group has its own version of this instrument, each played in a different style. A set of Ede gongs, for instance, includes 10 gongs, which can be stacked one inside the other. Sets of Ma and K’Ho gongs consist of 3 to 6 gongs, while a set of Ba Na gongs contains 6 to 9 gongs. The Rap Jarai, meanwhile, play sets of 21 gongs. Ede gongs are played by men, while it is women who play gongs in the Bih minority.

B: The gongs of the Ba Na have a powerful bass voice, like wind through the jungle, Jarai gongs are quick and light, inviting girls and boys to perform the traditional Xoan line-dance, in which they stand shoulder-to-shoulder. The Xe Dang gongs are fast and warlike, while those of the Ma and M’Nong seem to sob.

A: The gong music of the Ede people, meanwhile, tumbles out like a waterfall, as if voicing the longing of the tribe’s mythical founder Dam San. Gong music is one means by which the people express the beauty that surrounds them and celebrate the landscape of the Central Highlands.

B: Listening to a VOV broadcast on October 19, Dahmani Rachid of Algeria wrote: “Dear friends at Radio the Voice of Vietnam-English section. Thank you so much. It always encourages me to listen to your programs. Many interesting programs have caught my attention. I always enjoy your programs. I still like short-wave listening very much. Reception is good so I don’t have any major problems in listening to the English service. I’m following your radio on short waves and I visit your website frequently. I find your programs informative and outstanding”.

A: Thank you so much, Dahmani, for your compliments. They are a great source of encouragement for us. We’ll send you a QSL card to confirm your report.

B: Paul Walter reported listening to our broadcasts on October 8th at 0100UTC via Cypress Creek, South Carolina, on 7315 khz with SINPO of 35345 and on October 9th at 2330 UTC on 12020 khz with SINPO of 34233.

A: He wrote: “As always, your programs are enjoyable. I especially enjoy stories on Vietnam’s traditional culture and features on everyday life in Vietnam. Your broadcast on October 8 about a festival talking about Vietnamese costumes was the most enjoyable”.

B: Thank you, Paul. We highly appreciate your detailed reports and hope to hear more from you. We’ll confirm your reports with QSL cards.

A: We also received a reception report from Ricky Hein of the US who reported dead air on 6175 at 0100-0130 UTC and 0230-0300 UTC and picking up VOV broadcasts on 7315.

B: Ricky, thank you for your report. We’ll send you our winter frequency list soon so that you can tune in at the right time.

A: We’d like to acknowledge letters and emails from Victor Kravchenko of Ukraine, Sutomo Huang and Fachri of Indonesia, Mario Bonomelli of China, Richard Nowak of the US, SB Sharma, Sekar Thalainayar, and Atish Bhattachrya of India, Gerald Kallinger of Austria, Tjang Pak Ning of Indonesia, Richard Lemke of Canada, and Christian Altenius of Sweden. We’ll verify them with our QSL cards.

B: That’s all for today’s Letter Box. We welcome your feedback at: English section, VOV World Service, Radio the Voice of Vietnam, 45 Ba Trieu street, Hanoi, Vietnam. You can email us at englishsection@vov.org.vn. You’re invited to visit us online at www.vovworld.vn, where you can here both live and recorded programs. Good bye until next time.