UNEP data shows that the world produces 400 million cubic meters of plastic each year. (photo: Reuters) UNEP data shows that the world produces 400 million cubic meters of plastic each year. (photo: Reuters) |

An international legally binding instrument to combat plastic pollution

The idea of building a legally binding treaty to prevent and then completely eliminate plastic pollution was first agreed by countries at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) meeting in March 2022. The UN has scheduled 5 sessions and the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to finalize the treaty by the end of this year.

Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), said this will be the most important international agreement in the fight against climate change since the 2015 Paris Agreement, because plastic pollution is one of the world’s most serious environmental problems.

UNEP data shows that the world produces 400 million cubic meters of plastic each year and only about 10% gets recycled. Without restrictions, global plastic production will triple by 2060. As the world strives to wean itself off fossil fuels, oil companies have been turning to plastic as the key to their future.

The plastics industry accounts for 5% of annual global carbon emissions and that will increase to 20% by 2050 at current production rates. UNEP studies found about 13,000 chemicals in plastic products and about one fourth of those can be harmful to the environment and human health. Ms. Andersen said the treaty will give countries a comprehensive approach to solving plastic pollution.

“Not an instrument that deals with plastic pollution from recycling or waste management alone, the full life cycle. This means rethinking everything along the chain, from polymer to production, from product to packaging. We need to use fewer virgin materials, less plastic and no harmful chemicals. We need to ensure that we use, reuse, and recycle resources more efficiently. And dispose safely of what is left over,” said Andersen.

The previous three sessions have not made much progress. At the third session in Nairobi, Kenya last November, the draft treaty was expanded from 30 pages to 70 pages due to disagreements on multiple issues and the desire of some countries to record objections to what they considered overly ambitious goals.

At the on-going 4th session in Ottawa, 3,500 leaders of countries, corporations, and social organizations, scientists, and legal experts will try to narrow differences and reach agreement on at least some of the issues before the final session takes place in November this year in Busan city, South Korea.

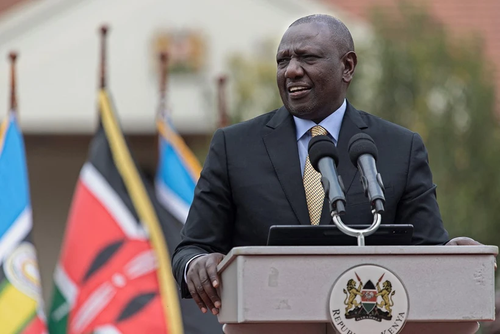

Kenyan President Willam Ruto (photo: AFP/VNA) Kenyan President Willam Ruto (photo: AFP/VNA) |

The treaty’s ambitions

According to the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee’s President Andres Gomez-Carrion, the biggest challenge is that the treaty’s level of ambition has not yet been decided. The countries that produce the most plastic and petrochemical products – Saudi Arabia, Iran, and China – oppose limiting plastic production, saying that it will increase global prices. That argument is supported by the Global Partnership for Plastic Circularity, which includes many plastic and chemical corporations from the US and the EU.

A group of 60 countries called the “High Ambition Alliance”, led by the EU and Japan, wants the treaty to limit plastic production globally, minimize the use of primary plastic, completely eliminate the use of single-use plastic products, and ban some chemical additives. The US, one of the biggest consumers of plastic products, supports the goal of ending plastic pollution by 2040, but allowing countries to follow their own roadmap rather than legally binding regulations.

Kenyan President Willam Ruto, the host of the third session and one of the most active members of the “High Ambition Alliance”, said that in order to reach a consensus, countries need to adopt a common approach and change their old habits of using plastic.

“To deal with plastic pollution, humanity must change. We must change the way we consume, the way we produce and how we dispose our waste. This is the reality of our world. Change is inevitable. This treaty, this instrument that we are working on, is the first domino in this change.”

In addition to governments’ opinions, the negotiations must take into account the opinions of the numerous multinational consumer goods corporations and lobbying groups attending the fourth session. Some observers think the treaty could be completed if corporations would make stronger commitments to reusing and limiting the production of plastic products.